By Yanliang Pan, January 15, 2024

On the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2023, the United States and the United Kingdom imposed unprecedented sanctions on subsidiaries of Russia’s state-owned nuclear corporation, Rosatom. Less than two months later, a group of G7 countries issued a joint statement pledging to “undermine Russia’s grip” on the world’s nuclear fuel supply chains (UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and Shapps 2023). Intentions aside, the pledge was overly optimistic: Western countries find themselves deeply dependent on Russian-origin nuclear fuel due to market and government failures in the past. And no present policy could bring about immediate diversification due to physical capacity constraints that will take producers time to overcome. Nor is accumulating a large stockpile of uranium going to solve the problem. To understand why, it is necessary first to survey the complex market for nuclear fuel.

Natural uranium takes the form of an oxide powder referred to as “yellowcake” when first extracted and refined. To turn it into the low-enriched uranium (LEU) suitable for use in a typical commercial reactor, the material must first become uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through a process known as “conversion” before going through enrichment. The enrichment process produces uranium with a higher concentration of the fissile uranium 235 isotope—the product that suppliers then use to fabricate fuel for specific reactors.

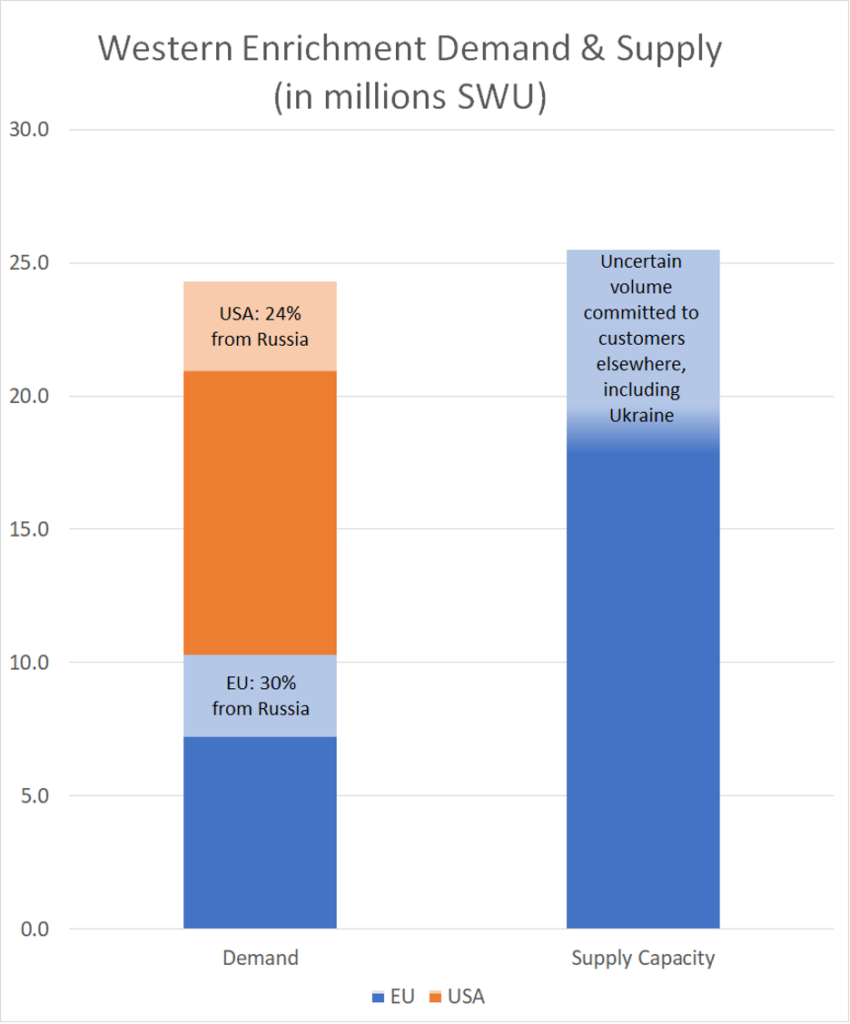

Rosatom currently meets 22.4 percent and 30 percent, respectively, of the European Union’s conversion and enrichment requirements (World Nuclear News 2023c). Meanwhile, US operators purchased 24 percent of their enrichment service requirements from Russia in 2022, or a total of 3.4 million separative work units (SWU), where SWU measures the amount of enrichment work done (US Energy Information Administration 2023, 2, 45). Such dependence not only prevents the application of full sanctions on the Russian nuclear industry, but it also subjects Western countries to various supply risks.

One risk is that Russia may interfere with the regular delivery of nuclear fuel for geopolitical leverage. Another risk comes from Western sanctions, which may hamper physical shipments. As an example, Canada’s revision in 2022 of its “special economic measures” on Russia led to delays in a Canadian carrier’s shipments of Russian LEU to the United States (Wood 2022). It took a waiver from the Canadian government to allow shipments to continue—and only for one year.

To mitigate these risks, Western governments have scrambled to subsidize domestic fuel cycle capacity and increase their strategic reserves. Months after the start of the war, the United Kingdom announced a Nuclear Fuel Fund providing “£75 million in grants to help preserve the UK front-end nuclear fuel cycle capability, in support of the British energy security strategy” (UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy 2022). Meanwhile, the US government is spending $75 million on the acquisition of a strategic uranium reserve (World Nuclear News 2022c), with the administration seeking an additional $1.5 billion to purchase backup LEU “to address potential future shortfalls in access to Russian uranium and fuel services” (White House 2022). Congress, for its part, has considered multiple bills to phase out imports of Russian nuclear fuel altogether.

Given the urgency of diversification from Russian supply, governments are understandably eager to accelerate the process using all means at their disposal. But not all such means are equally necessary or effective. Some target the wrong bottlenecks, such as by providing financing where the constraint is physical, or targeting the supply of natural uranium when the supply of conversion and enrichment services are tightest. Others simply duplicate adjustments that the market is already making, starting from market players’ voluntary severing of business ties with Rosatom due to reputational risks and supply uncertainties. As Tim Gitzel, the CEO of Canada-based uranium producer Cameco (formerly known as the Canadian Mining and Energy Corporation) noted: “It’s not a matter of ‘if’ Western markets will turn their backs on Russian nuclear fuel supply – but rather, ‘when,’ and how quickly” (World Nuclear News 2022b).

The key question therefore is not whether—or how—Western governments should compel companies to pivot away from Rosatom, but whether Western countries have sufficient fuel cycle capacity to enable such a pivot. The answer varies based on stages of the nuclear fuel cycle, and it is crucial to identify where the Western nuclear fuel supply capacity would be most constrained with Russia out of the picture.

Locating the bottlenecks

Russia is not among the world’s leading uranium miners. Most of its natural uranium comes from neighboring Kazakhstan, a former Soviet republic that declared independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union and as such is a source of supply to which Western companies have equal access—at least in theory. After years of oversupply, improving market conditions have enabled major uranium producers like Cameco and Kazatomprom to ramp up their output (Cameco 2022; Kazatomprom 2022). Even then, production at the largest uranium mines remains below full capacity, meaning there is more than enough potential for supply to expand alongside demand (World Nuclear News 2023a).

It is further downstream in the conversion and enrichment segments of the nuclear fuel cycle that Western countries are grappling with a potential shortfall. Such is Euratom’s prognosis, after analyzing the 10-year projected capacity and requirements of the “global West” (World Nuclear News 2023c). Industry analysis suggests that a shortfall may result from a disruption in Russian supply, which existing capacity is insufficient to replace (Euratom 2022). In quantitative terms, the European Union, excluding the United Kingdom, purchased 10.3 million SWU in 2021 whereas US nuclear operators have consistently acquired an annual 14 million SWU since 2020 (US Energy Information Administration 2023). Their requirements therefore add up to approximately 24.3 million SWU. On the supply side, the two main Western enrichers, France-based Orano and the British-German-Dutch consortium known as Urenco boast a combined 25.5 million SWU (Orano 2023; Urenco 2023a). However, part of their capacity is committed to long-term contracts with customers elsewhere, including in Asia, Africa, and Latin America (see Figure 1).

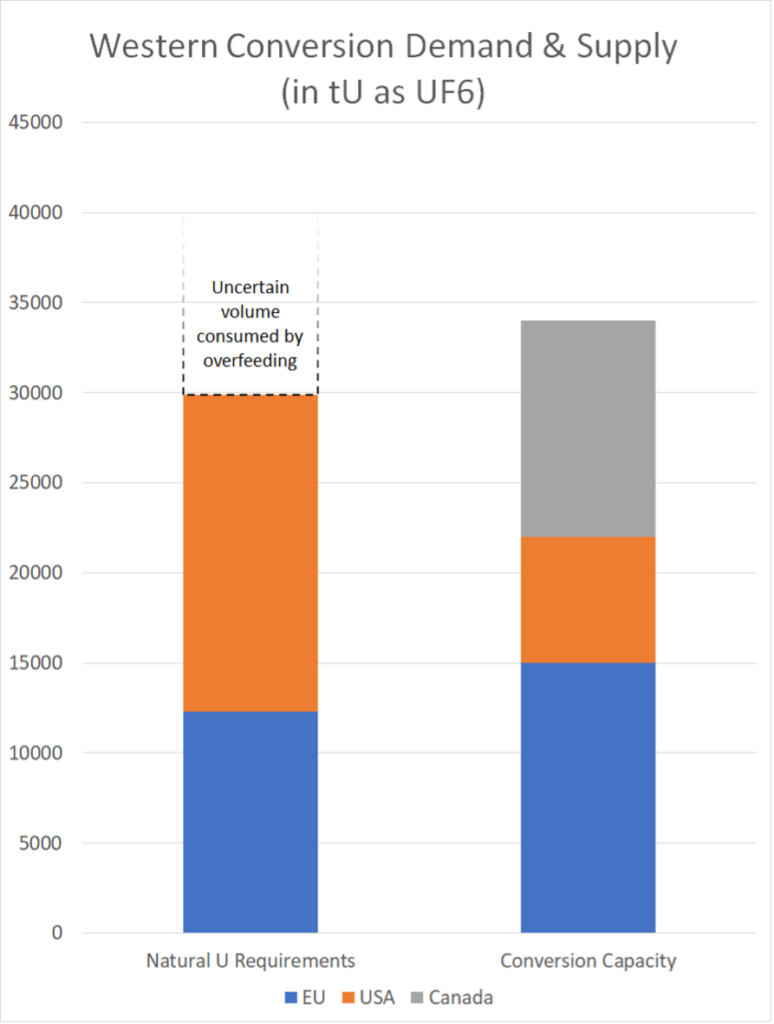

Uranium conversion supply is no less tight. Western conversion output is expected to add up to around 34,000 tons of uranium (tU, in the form of UF6) per year after ConverDyn’s Metropolis plant ramps up to its nominal capacity of 7,000 tU (Orano 2023; Chaffee 2022a) and Cameco’s Port Hope plant ramps up to 12,000 tU as pledged (Cameco 2023a) (see Figure 2). On the consumption side, however, natural uranium requirements in the United States and Europe alone add up to approximately 30,000 tU (World Nuclear Association 2023b; Euratom 2022). The actual conversion demand may be much higher with such operational adjustments as overfeeding—the practice of enriching more natural UF6 feed less intensively to reduce enrichment requirements. According to market sources, Urenco alone is expected to consume up to 10,000 tU of extra UF6 per year with the transition to overfeeding (Chaffee 2022a). The shortfall is obvious.

The war in Ukraine, which prompted diversification from Russian supply, has brought additional stresses upon Western capacity. For instance, Bulgaria’s two Soviet-design VVER reactors recently switched to Westinghouse- and Framatome-supplied fuel assemblies, requiring Urenco to supply the LEU necessary for the fabrication of such fuel and Cameco to provide the UF6 feed for enrichment (Urenco 2023b; World Nuclear News 2023d). In addition, Cameco has committed to supplying between 15,300 and 25,700 tU as UF6 to cover all of Ukraine’s conversion requirements from 2024 to 2035 (Cameco 2023a; 2023b). Cameco CEO Tim Gitzel called the supply contract “one of the largest and most important” in the company’s history (Nuclear Engineering International 2023). Like Bulgaria and Ukraine, the Czech Republic is set to begin receiving Western fuel assemblies for its six VVER reactors next year (Westinghouse Electric Company 2023). Finland and Sweden have also renounced Russian supply for their reactors, turning to US-based Westinghouse and France-based Framatome instead (Westinghouse Electric Company 2022; Vattenfall 2022).

The market responds

As the demand for Western conversion and enrichment grows, producers have taken market-driven decisions to expand their capacity. The two main Western enrichers, Orano and Urenco, are bringing their joint centrifuge fabrication facility back online to add new centrifuges to their enrichment plants. While Orano is planning to increase the capacity of its Georges-Besse II enrichment plant from 7.5 million to 11 million SWU (Nuclear Engineering International 2022b), Urenco, whose portfolio of orders grew by 25 percent during in 2022 alone (World Nuclear News 2023c), has said its priority for 2023 is to “refurbish and potentially expand” capacity at all four of its enrichment plants to meet its long-term supply obligations (Urenco 2023a, 9). In the view of the company, the investment in capacity is justified by “improving market fundamentals” for nuclear energy as well as diversification-driven demand.

There is just one catch. The delay in centrifuge fabrication means that the expansion of capacity will not materialize until 2028 (Chaffee 2022b; Wald 2023).

Meanwhile, US efforts to restore indigenous enrichment capacity are taking place at the initiative of Centrus, a US company that last produced its own LEU in 2013 at a now shuttered gaseous diffusion plant in Paducah, Kentucky. Centrus has since relied on Russian imports and inventories to satisfy its supply obligations. According to Centrus’ latest annual report, Russia’s Tenex is still the company’s largest enrichment supplier (Centrus Energy Corp. 2023). Under its contract, the US company is bound to purchase or pay for a minimum quantity of SWU from the Russian supplier every year until the end of 2028. In case of a supply disruption, alternative sources would only partially mitigate the near-term impact.

For now, market players are balancing supply and demand via short-term instruments such as the drawdown of inventories and overfeeding. Urenco has acknowledged engaging its inventories to satisfy additional purchase requests (Jennetta and Adelman 2022), saying there are still substantial “excess stocks” of enriched UF6 at its disposal (Wald 2023). Meanwhile, nuclear power plant owners and operators claim their own inventories are sufficient to provide a one- to two-year buffer (World Nuclear News 2022a)—not much in the slow-moving nuclear fuel business. Although government-held stocks, such as the US Energy Department’s 230-metric-ton stockpile of LEU, could provide a cushion of last resort, their volume is too small to respond to a prolonged disruption. The Department also maintains a stock of highly enriched uranium (International Panel on Fissile Materials 2023), though down-blending capacity is limited (Wald 2023). Moreover, only a small portion of the stock is available for civilian use, and high-assay, low-enriched uranium (HALEU) production takes precedence (US Department of Energy 2021).

In view of these tight margins, uranium enrichment producers are rushing to shift from underfeeding to overfeeding to save on their constrained enrichment capacity. For instance, Urenco says it is now “aggressively reversing the underfeeding which had consumed up to 30 percent of enrichment capacity previously” (Jennetta 2023b). Similarly, the buyers of enrichment services are instructing producers to flood their centrifuges with natural UF6 and enrich it less intensively to achieve the same LEU output with less SWU. The cost is higher requirements for conversion, the process that produces UF6. This reversal in market dynamics, in turn, has made conversion the hidden “bottleneck” to Western diversification and security of supply (World Nuclear News 2023e).

Past market and government failures

The Fukushima accident in 2011 precipitated a wave of reactor shutdowns as well as cancellations and delays in new reactor construction. The consequent fall in demand for nuclear fuel hit the suppliers of uranium conversion services especially hard. Prices remained low for many years due to an excess of supply in the conversion market. In 2017, US-based ConverDyn decided to suspend production at the country’s only conversion plant, located in Metropolis, Illinois, after the price of UF6 fell below the cost of production. To cover its long-term supply obligations, the company reportedly purchased some 45,000 tU of UF6 from the market between 2016 and 2021 (Jennetta 2021). Part of the volume came from the French nuclear fuel producer Orano, whose own conversion plant was delayed in its ramp-up to full capacity due to equipment issues.

The resulting UF6 supply gap was filled by the inventories of utilities, converters, and enrichers that had accumulated large stockpiles of UF6 in previous years. The consequence was a dramatic contraction of inventories. According to the US Energy Information Administration’s 2022 uranium market report, the volume of natural UF6 held by US nuclear power operators stood at 12,000 tU (US Energy Information Administration 2023), down more than 40 percent from 2016 (US Energy Information Administration 2020) and significantly below the country’s annual reactor requirement. A large portion of that volume is considered pipeline inventory, meaning the material already has somewhere to go, and only a small portion is actually available to enter the spot market. Earlier this year, ConverDyn president Malcolm Critchley indeed acknowledged that such mobile inventories of conversion and UF6 were already “gone” (Jennetta 2023b). Substantial excess stocks may only still exist in Asia (World Nuclear Association 2023a), though it is unknown for how long they will remain excess as Japan accelerates the restart of its shut down reactors and China continues to expand its civil nuclear fleet.

Government-held inventories offer even less insurance against possible supply disruptions. Much of the US government’s excess UF6 has gone to private contractors to pay for enrichment plant cleanup and HEU down-blending services. In 2008, the Energy Department’s excess uranium stockpiles included over 17,500 tU of natural UF6 (Moniz 2015). By the end of 2016, however, that number had declined to less than 5,300 tU, and transfers on an annual scale of 1,200 tU continued thereafter (Perry 2017). US uranium producers fiercely protested the transfers as they made already-poor market conditions worse. In fact, ConverDyn sued the Energy Department over the transfers, saying it would cause more than $40 million in income loss between 2014 and 2016 (Ostroff 2015), before it had to shut down its Metropolis conversion plant in 2017. Ironically, the department was responsible for more “dumping” in the US conversion market than Rosatom.

The latter has abided by a voluntary quota agreement that most US uranium producers and nuclear power operators favored extending as recently as December 2022, though some producers have called for further import restrictions in the past (International Trade Administration 2023; Majerus 2022). In April 2019, the US Commerce Department determined in response to a petition by US-based Ur-Energy and Energy Fuels that excessive imports of foreign-origin uranium products constituted a threat to national security. However, the Trump administration disagreed with that assessment and took no action other than the appointment of a nuclear fuel working group to investigate the matter (Fefer and Larson 2019). With little surprise, the working group suggested no drastic import restrictions, although it did recommend a build-up of government-held inventories starting in 2020 (US Department of Energy 2020, 16).

But it was not until late 2022 that the procurement of U3O8—a mixture of uranium oxides which is then converted to UF6—for the strategic reserve began (World Nuclear News 2022c). The Energy Department awarded a $14 million conversion contract to ConverDyn shortly after (Jennetta 2023a). But it was too little, too late. Conversion prices had shot up 400 percent by 2021, right when the Energy Department’s UF6 stockpiles had reached their minimum (TradeTech 2021). The war in Ukraine then doubled conversion prices once again (Cameco 2023a, 22). Procuring a strategic reserve now meant sequestering precious material amidst an acute shortage of supply.

The same applies to current initiatives to expand US strategic stockpiles of LEU. Following the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in August of 2022, the Biden administration asked Congress to allocate another $1.5 billion for “the acquisition and distribution of low-enriched uranium (LEU) and high-assay LEU (HALEU) … to reduce the reliance of the United States and friendly foreign countries on nuclear fuels from the Russian Federation and other insecure sources of LEU and HALEU” (White House 2022). Meanwhile, members of Congress have advanced multiple bills seeking a similar sum to expand the 230-metric-ton American Assured Fuel Supply (Chalfant 2022; McMorris Rodgers 2023). It is unclear what purpose such acquisitions would serve other than sequestering precious material from the market. Major operators will not be able to rely on the federal government’s highly limited reserve to shield themselves against a prolonged supply disruption any time soon. And even if reserves were to quickly expand to form a meaningful cushion, there is no guarantee it would enhance supply security, especially if the government releases its stocks in ways that disrupt the market or create a moral hazard problem that renders nuclear operators less diligent in ensuring their own continuity of supply.

To be sure, there was a time for expanding strategic reserves—such as when supply outstripped demand and domestic producers needed the demand assurance provided by government purchases to make the necessary investment in capacity. But this rationale is no longer as relevant today. Western enrichment companies have made clear that no capacity expansion can materialize before 2028 regardless of the demand picture. This means their ability to replace Russian supply will be constrained in the near term. Meanwhile, conversion suppliers have already made ambitious capacity commitments in response to market signals, obviating the need for demand assurance. Cameco, for instance, plans to raise the UF6 output at its Port Hope facility to 12,000 tU to satisfy long-term contracts, which have grown by record volumes (Cameco 2023a).

Help the market adjust itself

Producers can make market-driven decisions to satisfy their supply obligations. Similarly, utilities know what risks of supply shortage they face, what degree of diversification they need, and what instruments of insurance are available. One effective approach therefore is for governments to offer the incentives and certainty that producers need to address their own supply risks via industry best practices, just as they have always done. After all, geopolitics is a challenge that nuclear fuel market players have long had to navigate (Nuclear Engineering International 2022a). Whether through inventories, options, loans, swaps, or a flexible combination of these instruments, industry players know how they can best hedge against supply disruptions, provided governments offer the right incentives and sufficient certainty for them to do so.

Incentives can take the form of inventory requirements—or clear signals that the government’s bailout reserves will go first to those players that have done their own due diligence to ensure security of supply.

Meanwhile, policy forecasts can serve to inject more certainty into the market. Governments should keep industry clearly informed as to the range of possible restrictions against Russian fuel supply ahead of time, sharing ongoing deliberations both within and beyond the executive branch. If restrictions are forthcoming, producers will need reasonably certain forecasts on how much Russian supply will be allowed back into the Western market once the geopolitical crisis expires so as to avoid excess capacity investment (Coyne 2023). Any forecasts of future policy actions should be moderate and steady insofar as market panic would be counterproductive to supply security.

An additional instrument is macro guidance. Through the publication of advisories that highlight prominent supply risks while providing accurately surveyed production, demand, and inventory statistics across the global market, governments can enable industry players to make rational market-balancing decisions.

Future supply and demand in the conversion and enrichment markets will depend on a host of factors. These include the evolution of the war in Ukraine, the expansion of non-Western fuel cycle capacity, the schedule of reactor outages due to lifetime extension, and the rate at which advanced reactors, fuel, and fuel production technologies enter commercial service, just to name a few. Given these complex dynamics, governments should not assume they know better than the market does about when, how much, and in which stage of the nuclear fuel cycle investments are needed.

To be sure, the production of HALEU, for which market demand is still highly uncertain, will continue to require public investment (World Nuclear News 2023b). However, when it comes to traditional uranium conversion and enrichment, not only are government funds unlikely to accelerate capacity expansion in the short term, but any knee-jerk supply subsidy in response to the Ukraine shock risks creating excess long-term capacity that will atrophy in the absence of sustained demand on the market. Recognizing the limits of what they can—and can’t—accomplish via stockpiles and subsidies, Western governments would do well to incentivize and assist market players protecting their conversion and enrichment supply chains until new capacity can be added. Only then will they be able to really do something about Russia’s “grip” on the world’s nuclear fuel supply chains without putting their own energy security at risk.

Acknowledgments

This article benefitted immensely from the comments of Miles Pomper at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Experts at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center contributed additional background information. The author takes responsibility for all factual claims and views presented.

References

Cameco. 2022. “Cameco Produces First Packaged Pounds Following McArthur River/Key Lake Restart.” November 9. https://www.cameco.com/media/news/cameco-produces-first-packaged-pounds-following-mcarthur-river-key-lake-res

Cameco. 2023a. 2022 Annual Report. https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets-us-west-2/annual/cameco-2022-annual-report.pdf

Cameco. 2023b. “CCO and Energoatom Agree on Commercial Terms to Supply Ukraine’s Full Natural UF6 Needs through 2035.” February 8. https://www.cameco.com/media/news/cco-and-energoatom-agree-on-commercial-terms-to-supply-ukraines-full-natura

Centrus Energy Corp. 2023. Centrus Form 10-K. https://investors.centrusenergy.com/static-files/9c69d593-1dbd-4b90-98d6-47232a99426d

Chaffee, P. 2022a. “Nuclear Fuel: Western Suppliers Prepare for Sudden Bull Market.” Energy Intelligence. March 25. https://www.energyintel.com/0000017f-9d96-db3b-a9ff-bdfe14e90000

Chaffee, P. 2022b. “Interview: Orano’s Peythieu on Navigating Market in ‘Fog of War.’ ” Energy Intelligence. September 23, 2022. https://www.energyintel.com/00000183-59a2-db08-a79f-59f7ecc60000

Chalfant, M. 2022. “White House Asks Congress for $13.7B in Ukraine-Related Funding.” The Hill. September 2. https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/3625876-white-house-asks-congress-for-13-7b-in-ukraine-related-funding/

Coyne, E. 2023. “Uranium Update from Per’s Cabin.” Sprott. June 27. https://sprottetfs.com/insights/podcast-uranium-update-from-pers-cabin/

Euratom. 2022. Euratom Supply Agency Annual Report 2021. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://euratom-supply.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-12/Euratom%20Supply%20Agency%20-%20Annual%20report%202021%20-%20Corrected%20edition.pdf

Fefer, R.F., and L.N. Larson. 2019. Section 232 Investigation: Uranium Imports. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11145

International Panel on Fissile Materials. 2023. “Fissile Material Stocks.” April 29. https://fissilematerials.org/

International Trade Administration. 2023. “Uranium From the Russian Federation; Final Results of the Expedited Fifth Sunset Review of the Suspension Agreement.” Federal Register. January 3. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/01/03/2022-28532/uranium-from-the-russian-federation-final-results-of-the-expedited-fifth-sunset-review-of-the

Jennetta, A. 2021. “Metropolis Restart Decision Driven by Conversion Supply Gap: Official.” Platts Nucleonics Week 62 (18).

Jennetta, A. 2023a. “US DOE Awards $14 Million to US Uranium Converter for Reserve Program.” Platts Nuclear Fuel48 (1).

Jennetta, A. 2023b. “Recent Trends in Uranium Conversion, Enrichment Markets Will Continue in 2023: Executives.” Platts Nucleonics Week 64 (4).

Jennetta, A., and O. Adelman. 2022. “Uranium Enrichment Capacity Expansion Program Top Priority for 2023: Urenco.” Platts Nucleonics Week 63 (51).

Kazatomprom. 2022. “Kazatomprom 3Q22 Operations and Trading Update.” October 26. https://www.kazatomprom.kz/en/media/view/operatsionnie_rezultati_deyatelnosti_ao_nak_kazatomprom_za_3_kvartal_2022_goda

Majerus, R. 2022. Issues and Decision Memorandum for the Final Results of the Fifth Sunset Review of the Agreement Suspending the Antidumping Investigation on Uranium from the Russian Federation. Washington, D.C.: International Trade Administration. https://access.trade.gov/public/FRNoticesListLayout.aspx

McMorris Rodgers, C. 2023. Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1042/text

Moniz, E.J. 2015. Analysis of Potential Impacts of Uranium Transfers on the Domestic Uranium Mining, Conversion, and Enrichment Industries. Washington, DC: US Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/2015-secretarial-determination

Nuclear Engineering International. 2022a. “World Nuclear Fuel Conference Report.” June 22. https://www.neimagazine.com/features/featureworld-nuclear-fuel-conference-report-9793490/

Nuclear Engineering International. 2022b. “Orano to Increase Uranium Enrichment Capacity.” October 14. https://www.neimagazine.com/news/newsorano-to-increase-uranium-enrichment-capacity-10086612/

Nuclear Engineering International. 2023. “Ukraine’s Energoatom Signs Agreements with Cameco for Fuel Supplies.” March 22. https://www.neimagazine.com/news/newsukraines-energoatom-signs-agreements-with-cameco-for-fuel-supplies-10694716/

Orano. 2023. “Tricastin.” https://www.orano.group/en/nuclear-expertise/orano-s-sites-around-the-world/uranium-transformation/tricastin/expertise

Ostroff, J. 2015. “DOE Uranium Transfer Plan Fails to Assess Economic Harm: ConverDyn.” Platts Nucleonics Week 56 (23).

Perry, R. 2017. Analysis of Potential Impacts of Uranium Transfers on the Domestic Uranium Mining, Conversion, and Enrichment Industries. Washington, DC: US Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/secretarial-determination-april-2017

TradeTech. 2021. “Nuclear Market Review.” Sprott. August 20. https://sprott.com/media/4209/nmr210820.pdf

UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. 2022. “Nuclear Fuel Fund (NFF): Request for Information (Closed).” July 19. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nuclear-fuel-fund-nff

UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, and Grant Shapps. 2023. “New Nuclear Fuel Agreement alongside G7 Seeks to Isolate Putin’s Russia.” April 16. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-nuclear-fuel-agreement-alongside-g7-seeks-to-isolate-putins-russia

Urenco. 2023a. Annual Report and Accounts 2022. https://www.urenco.com/cdn/uploads/supporting-files/Urenco_AR2022.pdf

Urenco. 2023b. “Urenco Signs Nuclear Fuel Agreement to Support Bulgaria Diversification Efforts.” April 20. https://www.urenco.com/news/global/2023/urenco-signs-nuclear-fuel-agreement-to-support-bulgaria-diversification-efforts

US Department of Energy. 2020. “Restoring America’s Competitive Nuclear Energy Advantage: A Strategy to Assure U.S. National Security.” https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/04/f74/Restoring%20America%27s%20Competitive%20Nuclear%20Advantage-Blue%20version%5B1%5D.pdf

US Department of Energy. 2021. “Request for Information (RFI) Regarding Planning for Establishment of a Program To Support the Availability of High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) for Civilian Domestic Research, Development, Demonstration, and Commercial Use.” Federal Register. December 14. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/12/14/2021-26984/request-for-information-rfi-regarding-planning-for-establishment-of-a-program-to-support-the

US Energy Information Administration. 2020. 2019 Uranium Marketing Annual Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Energy. https://www.eia.gov/uranium/marketing/archive/umar2019.pdf

US Energy Information Administration. 2023. 2022 Uranium Marketing Annual Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Energy. https://www.eia.gov/uranium/marketing/pdf/2022%20UMAR.pdf

Vattenfall. 2022. “Vattenfall Secures Long-Term Nuclear Fuel Supply.” May 5. https://group.vattenfall.com/press-and-media/pressreleases/2022/vattenfall-secures-long-term-nuclear-fuel-supply

Wald, M. 2023. “On the Verge of a Crisis: The U.S. Nuclear Fuel Gordian Knot.” Nuclear Newswire. April 15. https://www.ans.org/news/article-4909/on-the-verge-of-a-crisis-the-us-nuclear-fuel-gordian-knot/

Westinghouse Electric Company. 2022. “Helping Finland to Secure Its Energy Future.” November 22. https://info.westinghousenuclear.com/news/helping-finland-secure-energy-future

Westinghouse Electric Company. 2023. “Westinghouse Reinforces Its Commitment to Energy Security in Czech Republic.” March 29. https://info.westinghousenuclear.com/news/westinghouse-reinforces-its-commitment-to-energy-security-in-czech-republic

White House. 2022. “FY 2023 Continuing Resolution (CR) Appropriations Issues.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/CR_Package_9-2-22.pdf

Wood, J. 2022. “A Global Realignment.” Nuclear Engineering International. October 20. https://www.neimagazine.com/features/featurea-global-realignment-10102424/

World Nuclear Association. 2023a. “Supply of Uranium.” May. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/supply-of-uranium.aspx

World Nuclear Association. 2023b. “World Nuclear Power Reactors & Uranium Requirements.” July. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/facts-and-figures/world-nuclear-power-reactors-and-uranium-requireme.aspx

World Nuclear News. 2022a. “Calm Approach the Right Strategy for Energy Security, Says Panel.” April 28. https://world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Calm-approach-the-right-strategy-for-energy-securi

World Nuclear News. 2022b. “Cameco Promises Patience as Uranium Market Realigns.” May 5. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Cameco-promises-patience-as-uranium-market-realign

World Nuclear News. 2022c. “First Contracts Awarded for US Strategic Uranium Reserve.” December 16. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/First-contracts-awarded-for-US-strategic-uranium-r

World Nuclear News. 2023a. “Cameco Reaps Benefits of ‘best-Ever’ Fuel Market Fundamentals.” February 10. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Cameco-reaps-benefits-of-best-ever-fuel-market-fun

World Nuclear News. 2023b. “Centrus on Track for HALEU Demonstration by Year-End.” February 10. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Centrus-on-track-for-HALEU-demonstration-by-year-e

World Nuclear News. 2023c. “Market Dynamics under Spotlight at WNFC 2023.” April 20. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Market-dynamics-under-spotlight-at-WNFC-2023

World Nuclear News. 2023d. “Urenco, Cameco Sign Supply Deals for Bulgaria’s Kozloduy.” April 21. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Urenco,-Cameco-sign-10-year-deals-with-Bulgaria-s

World Nuclear News. 2023e. “Fuel Cycle Players Need Certainty to Support Future Nuclear Growth: Panel.” September 8. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Fuel-cycle-players-need-certainty-to-support-futur